Transplanting the East in Europe

Chinese influences, such as pagodas, paintings and ancient temples, inspired a desire in elitists for exotic garden designs, Zhao Xu reports.

Chambers traveled to China as a trading agent for the Swedish East India Company.

In 1603, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) captured a Portuguese galleon near Singapore, richly laden with Chinese goods, including porcelain adorned with intricate garden scenes. The episode revealed not only the inevitable clash between a rising maritime power and an established one, but also the immense allure of Chinese wares.

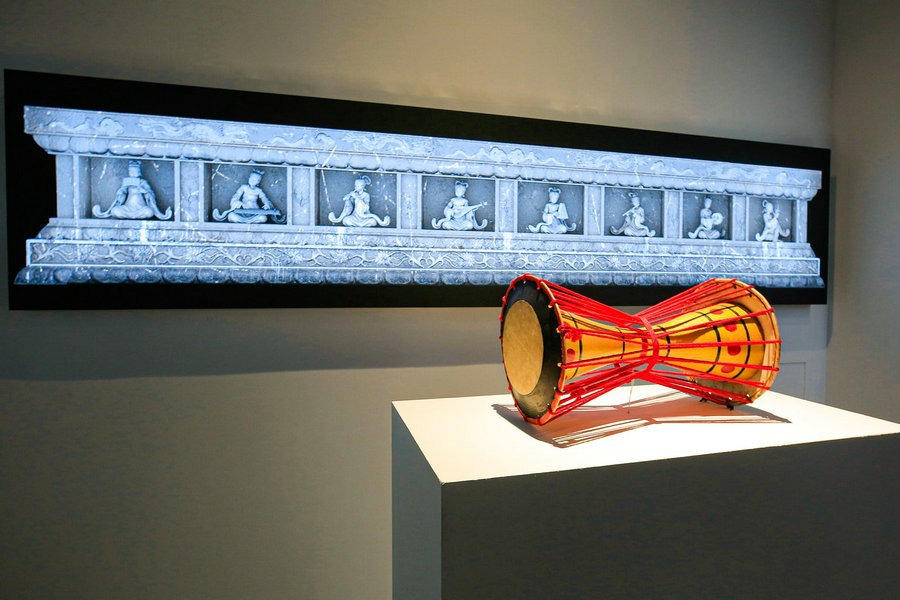

Chinoiserie emerged and reached its peak in 18th-century Europe as a romanticized reinvention of China, reflecting the era's fascination with the exotic.

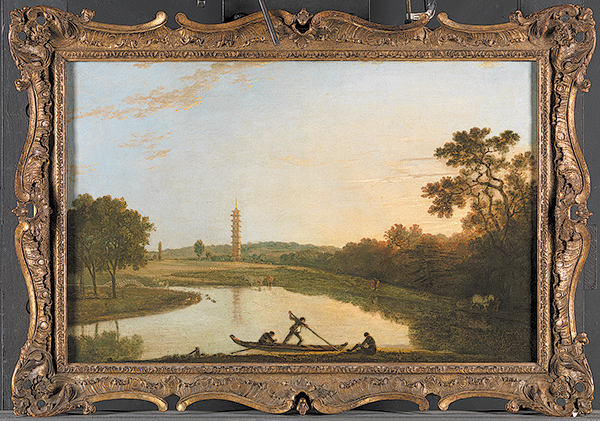

This aesthetic preference found expression in garden designs through the addition of Chinese-inspired "architectural follies" — such as the pagoda — into otherwise European landscapes.

Superficial as it may seem, the transplantation of the Chinese garden into European soil unfolded amid profound social, political and philosophical transformations, serving as both a catalyst for and a reflection of those changes, says Lyu.

"Parallel to the rise of Chinoiserie was the emergence of the English garden as a distinct style — an antithesis to the formal, symmetrical French gardens where everything was arranged along central axes," says Lyu, pointing to Versailles, the ultimate showcase of French Baroque architecture.

With its grand scale, strict geometry, and long avenues and sightlines radiating from the palace, Versailles proclaimed the monarch's absolutist power over man and nature, something the British would come to reject in their search for a national identity, in a century that included the execution of King Charles I of England and the ensuing establishment of a constitutional monarchy.

As a political and cultural statement, the English garden embraced a more naturalistic, irregular and free-flowing design, allowing for meandering paths, gently rolling lawns, and asymmetrical vistas that suggest a more harmonious relationship between man and nature.

All that sounds familiar to someone living in 17th and 18th-century China, when garden-building became a fad among the literati elite and in the city of Suzhou, which boasted a long tradition of literati culture and became the place for Chinese gardens.

Of the many exquisite gardens built in the city throughout ancient China, one rises head and shoulders above the rest — Zhuozheng Yuan, or the Humble Administrator's Garden, next door to the Suzhou Museum.

Its first owner, Wang Xianchen, who constructed the garden between 1509 and 1525, had endured enough trials in court life to deem himself "zhuozheng", or clumsy with politics. Resigning from office at 40, Wang spent the rest of his life in relative seclusion in his manicured version of nature, which comprised meandering waterways, sculpted rockeries, contorted trees, and pavilions and halls of serene elegance.