How Shanghai became safe harbor for Jews

Jews besieged foreign consulates in Vienna day after day. Obtaining the "proof of emigration" required by Nazi authorities became a desperate and agonizing quest for survival. Here is how one refugee described it:

"Visas! We began to live visas day and night. When we were awake, we were obsessed by visas. We talked about them all the time. Exit visas. Transit visas. Entrance visas. Where could we go? During the day, we tried to get the proper documents, approvals, stamps. At night, in bed, we tossed about and dreamed about long lines, officials, visas. Visas."

At this time, foreign diplomats like my father could play a crucial role in helping Jews, but none did so. Many of their countries, and nearly all of the 32 Western nations participating in the Evian Conference in July 1938, had anti-immigration policies and were unwilling to open their doors to Jewish refugees.

The father of 11-year-old Lotte Lustig, for example, obtained an American telephone directory, and Lotte wrote to all the people who bore the same last name — Lustig — asking them to sponsor her family to the US.None agreed. The Lustigs obtained Shanghai visas from my father's consulate on Oct 18, 1938, a day when at least 106 such visas were issued, and escaped to Shanghai.

My father came from a generation of Chinese who keenly felt the 100 years of humiliation that China had suffered under foreign imperialism, so he could not stand idly by. "Seeing the tragic plight of the Jews, it is only natural to feel deep compassion, and from a humanitarian standpoint, to be impelled to help them," he would later recall.

"I used every means possible, saving who-knows-how-many Jews!"

However, unlike his diplomatic peers, my father faced some daunting obstacles as China's representative in 1938. The first was access to his home country, much of which, including all of its ports of entry, had been under Japanese occupation since 1937. Any entry visa issued by a Chinese diplomat would certainly not be recognized by the Japanese occupiers.

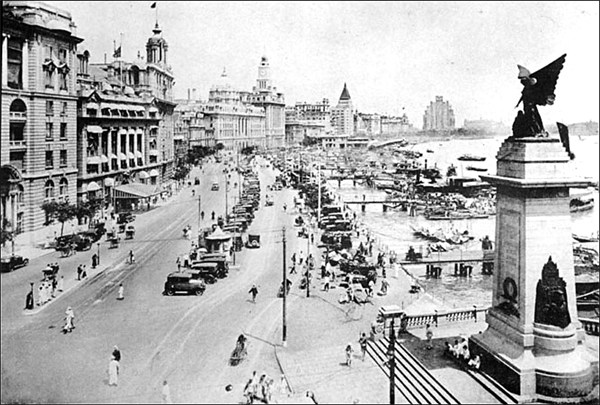

There was, however, one loophole: the port of Shanghai. Following the Opium War of 1840, portions of Shanghai had been carved up by the foreign imperialist powers into extraterritorial "concessions". The Japanese invasion in 1937 occupied the Chinese portions of the city, but the International Settlement and the French Concession remained untouched enclaves.